Perhaps one of the greatest challenges in a believer’s life is learning how to reconcile our human desire for recognition with the divine virtue of humility that God calls us to adopt.

Indeed, the human temptation to glorify ourselves is as old as the story of the Tower of Babel, where God’s people became eager to receive their own honor and recognition: “Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves” (Genesis 11:4).

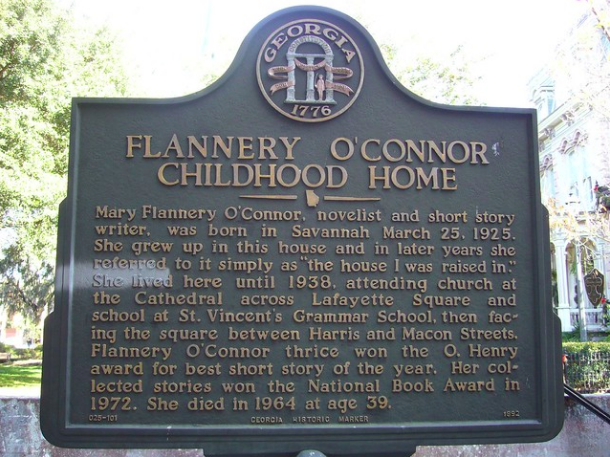

Similar sentiments for wanting to be somebody can be found throughout history, a most poignant example in Flannery O’Connor’s (1925-1964) personal journal, written while earning her Master of Fine Arts degree at the University of Iowa from January 1946 through September 1947.

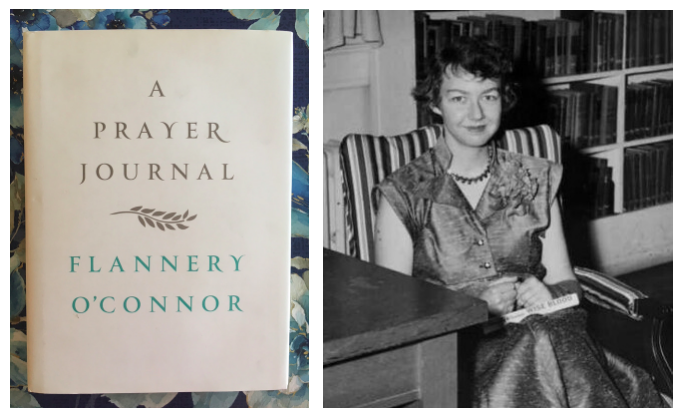

Compiled in A Prayer Journal (2013), with an introduction by scholar and friend W.A. Sessions, O’Connor’s entries reveal the internal battle we can so often face, between our desire to be regarded by the world and surrendered to God’s will.

Using a beautiful metaphor, the aspiring novelist writes at just 21 years of age:

“Dear God, I cannot love Thee the way I want to. You are the slim crescent of a moon that I see and my self is the earth’s shadow that keeps me from seeing all the moon. The crescent is very beautiful and perhaps that is all one like I am should or could see; but what I am afraid of, dear God, is that my self shadow will grow so large that it blocks the while moon, and that I will judge myself by the shadow that is nothing.

I do not know you God because I am in the way. Please help me to push myself aside.”

She struggles to do just that, wanting to subdue her ego while desiring it to be fed:

“I want very much to succeed in the world with what I want to do. I have prayed to You about this with my mind and my nerves on it and strung my nerves into a tension over it and said, ‘oh God please,’ and ‘I must,’ and ‘please, please.’ I have not asked You, I feel, in the right way. Let me henceforth ask you with resignation – that not being or meant to be a slacking up in prayer but a less frenzied kind – realizing that the frenzy is caused by an eagerness for what I want and not a spiritual trust.”

Her internal dialogue captures the maddening intensity of these competing desires:

“How can I live – how shall I live. Obviously the only way to live right is to give up everything. But I have no vocation & maybe that is wrong anyway. But how [to] eliminate this picky fish bone kind of way I do things – I want so to love God all the way. At the same time I want all the things that seem opposed to it – I want to be a fine writer.”

Her desperation is felt most poignantly in a passage that becomes strangely unsettling when we consider her untimely death from lupus at the age of 39:

“Dear Lord please make me want You. It would be the greatest bliss. Not just to want You when I think about You but to want You all the time, to think about You all the time, to have the want driving in me, to have it like a cancer in me. It would kill me like a cancer and that would be the Fulfillment.”

Trying to reorient her perspective, she recognizes who is in control:

“Any success will tend to swell my head – unconsciously even. If I ever do get to be a fine writer, it will not be because I am a fine writer but because God has given me credit for a few of the things He kindly wrote for me. Right at present this does not seem to be His policy. I can’t write a thing. But I’ll continue to try – that is the point. And at every dry point, I will be reminded Who is doing the work when it is done & Who is not doing it at that moment.”

And continues her pleas to God for deliverance from self:

“I don’t want to be doomed to mediocrity in my feeling for Christ. I want to feel. I want to love. Take me, dear Lord, and set me in the direction I am to go.”

Then she makes a comical request:

“What I am asking for is really very ridiculous. Oh Lord, I am saying, at present I am cheese, make me a mystic, immediately. But then God can do that – make mystics out of cheeses. But why should He do it for an ingrate slothful & dirty creature like me. I can’t stay in the church to say a Thanksgiving even[,] and as for preparing for Communion the night before – thoughts all elsewhere. The rosary is mere rote for me while I think of other and usually impious things. But I would like to be a mystic and immediately.”

And concludes the entry with a statement all too common for believers in a state of despair:

“If I could only hold God in my mind. If I could only always just think of Him.”

We see her mind also struggle to understand the concept of heaven:

“I dread, Oh Lord, losing my faith. My mind is not strong. It is a prey to all sorts of intellectual quackery. I do not want it to be fear which keeps me in the church. I don’t want to be a coward, staying with You because I fear hell. I should reason that if I fear hell, I can be assured of the author of it. But learned people can analyze for me why I fear hell and their implication is that there is no hell. But I believe in hell. Hell seems a great deal more feasible to my weak mind than heaven. No doubt because hell is a more earthly-seeming thing. I can fancy the tortures of the damned but I cannot imagine the disembodied souls hanging in a crystal for all eternity praising God. It is natural that I should not imagine this.”

But she has no trouble forming a funny, clever idea:

“If we could accurately map heaven some of our up-&-coming scientists would begin drawing blueprints for its improvement, and the bourgeois would sell guides 10c the copy to all over 65. But I do not mean to be clever although I do mean to be clever on 2nd thought and like to be clever & want to be considered so.”

And asks for the desire to give up all earthly things:

“But the point more specifically here is, I don’t want to fear to be out, I want to love to be in; I don’t want to believe in hell but in heaven. Stating this does me no good. It is a matter of the gift of grace. Help me to feel that I will give up every earthly thing for this.”

But maybe not everything:

“I do not mean becoming a nun.”

Her final entry reveals her despondency; an anticlimactic end to her fervent attempt to fully consecrate herself to God:

“My thoughts are so far away from God. He might as well not have made me. And the feeling I egg up writing here lasts approximately a half hour and seems a sham. I don’t want any of this artificial superficial feeling stimulated by the choir. Today I have proved myself a glutton – for Scotch oatmeal cookies and erotic thought. There is nothing left to say of me.”

There was, in fact, a lot left to say:

O’Connor’s prayers to “be a good writer” would be answered. She would go on to produce what is considered some of the greatest fiction in American literature, writing two novels (Wise Blood, 1952 and The Violent Bear it Away, 1960) and 32 short stories (A Good Man is Hard to Find, 1955, being one of the most widely read and highly acclaimed short stories of all time). Her posthumously compiled The Complete Stories (1971) won the 1972 U.S. National Book Award for fiction.

Indeed, with writings infused with religious undertones, making her one of the strongest Roman Catholic apologists of the 20th century, O’Connor’s widespread acclaim leaves one wondering if she wasn’t, in fact, what she truly longed to be – an instrument of God.

As she prayed in one entry:

“Don’t let me ever think, dear God, that I was anything but the instrument for Your story – just like the typewriter was mine.”

Wow, that was very good – really intense!!!