While “social distancing” and quarantine became an uncomfortable, inconvenient reality for many of us during the COVID-19 pandemic, the opportunity it afforded us to simply be – to stay with oneself, devoid of distractions – is perhaps one of the greatest blessings ushered in by what might otherwise be described as a global crisis.

Indeed, if the Desert Fathers – a term used to characterize the first Christian hermits of the 4th century AD – were alive today, I suspect they would rejoice in the opportunity to practice solitude, unwelcome as it may be, believing as they did that solitude is a gateway to the inner peace and fulfillment we so often seek in the distractions of the world.

As one of their many sayings goes, recorded in Thomas Merton’s book, The Wisdom of the Desert (1960):

“A certain brother went to Abbot Moses in Scete, and asked him for a good word. The elder said to him: ‘Go, sit in your cell, and your cell with teach you everything.’”

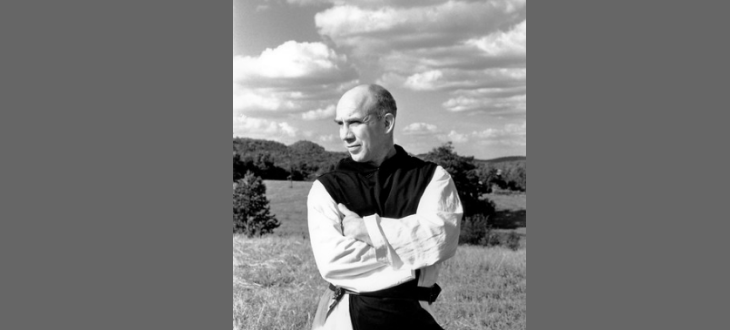

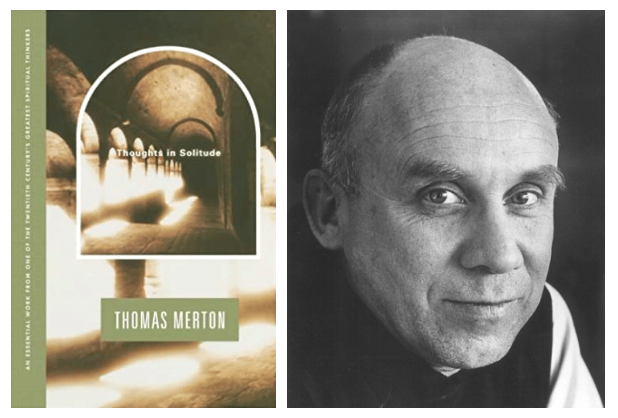

Imprisoned in a cell as it might feel, solitude, it turns out, can be a pleasurable existence – a necessity, even, in creating a healthy society, or so suggests Thomas Merton (1915-1968) in his book, Thoughts in Solitude (1958).

The Trappist monk, who spent 27 years in the most ascetic Roman Catholic monastic order, writes:

“Society depends for its existence on the inviolable personal solitude of its members. Society, to merit its name, must be made up not of numbers, or mechanical units, but of persons. To be a person implies responsibility and freedom, and both these imply a certain interior solitude, a sense of personal integrity, a sense of one’s own reality and of one’s ability to give himself to society – or to refuse that gift.”

Indeed, solitude is integral to fostering virtuous human attributes:

“When men are merely submerged in a mass of impersonal human beings pushed around by automatic forces, they lose their true humanity, their integrity, their ability to love, their capacity for self-determination. When society is made up of men who know no interior solitude it can no longer beheld together by love: and consequently it is held together by a violent and abusive authority.”

In solitude, we develop the ability to see things more clearly:

“The solitary life, being silent, clears away the smoke-screen of words that man has laid down between his mind and things. In solitude we remain face to face with the naked being of things. And yet we find that the nakedness of reality which we have feared, is neither a matter oft error nor for shame. It is clothed in the friendly communion of silence, and this silence is related to love. The world our words have attempted to classify,to control and even to despise (because they could not contain it) comes close to us, for silence teaches us to know reality by respecting it where words have defiled it.”

And develop a deeper appreciation for life:

“The great work of the solitary life is gratitude. The hermit is one who knows the mercy of God better than other men because his whole life is one of complete dependence, in silence and in hope, upon the hidden mercy of our Heavenly Father. The further I advance into solitude the more clearly I see the goodness of all things.”

Solitude, then, is a gateway to gratitude, which is the heart of the Christian life:

“To be grateful is to recognize the Love of God in everything He has given us – and He has given us everything. Every breath we draw is a gift of His love, every moment of existence is a grace, for it brings with it immense graces from Him. Gratitude therefore takes nothing for granted, is never unresponsive, is constantly awakening to new wonder and to praise of the goodness of God. For the grateful man knows that God is good, not by hearsay but by experience. And that is what makes all the difference.”

[…]

“Gratitude is therefore the heart of the solitary life, as it is the heart of the Christian life.”

Thomas Merton is one among many spiritual contemplatives that have argued for the deliberate practice of solitude. Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855), in his densely packed discourse, The Lily of the Field and the Bird of the Air, urges us to exercise silence before God. For silence, he writes, “expresses respect for God, for the fact that it is he who rules and he alone to whom wisdom and understanding belong.”

Furthermore, the Dalai Lama, who has endured a life of exile, has found that the daily practice of intentional silence fosters gratitude, which he characterizes as one of the “four qualities of the heart” that lead to joyful living.